History of package tzf

The basic development work of tzf and related projects has basically stabilized. In the previous article, there are sporadic information about the development and design process:

- 2022-05-29, 在 Go 中将经纬度转时区

- 2022-08-01, Python 中经纬度转时区新的选择

- 2022-08-27, 用 Go 编写 Python 扩展

- 2022-09-10, tzf 预览图制作

- 2022-11-24, tzfpy Rust 重写

This article is the final summary, from the start-up of the project to the gradual optimization and evolution.

We used to use timezonefinder to convert longitude&latitude to timezone names. And it could be very slow around polygon borders. In previous versions, the query of the edge of the polygon may need to be 200ms or even 800ms. In version @6.1.0 it switched to the Ray Cast algorithm implemented by C, but it was still not so stable. The time-consuming gap between the fastest and slowest was relatively large, so I tried to develop a package library in the longitude and latitude transition time zone by myself.

I have the experiences about convert GPS coordinates to China’s administrative division, a Chinese introduction can be accessed here, which including the problem of Point in polygon and Ray casting algorithm. So in theory, all I need is the timezone’s shapes data. We need great thanks for @evansiroky who maintained a repo names timezone-boundary-builder that keep tracking Timezone Database’s release while maintaining GeoJSON and ShapeFile data files release for years, and data files are licensed under the Open Data Commons Open Database License (ODbL), so we can these file legally.

I choose to process GeoJSON file because I’m more familiar with it. This file is about 45MB after compression and 155MB after decompression, which is too large for the project, so the first problem is how to reduce the data volume.

One of the simplest ideas is to store it in a more efficient binary encoding

format. My teams are familiar with Protocol Buffers, so I wrote the

tzinfo.proto

file. It should be noted that in GeoJSON’s definition of

RFC 7946, Polygon is a lot of curve

shapes, the first of which represents the external shape of the polygon, and the

rest are internal shapes, that is, the hole in the middle of the polygon. This

kind of data is repeated repeated Point with Protocol Buffers syntax, which is

not supported by Protocol Buffers. It needs to be split into two fields to

represent:

message Point {

float lng = 1;

float lat = 2;

}

message Polygon {

repeated Point points = 1;

repeated Polygon holes = 2;

}

message Timezone {

repeated Polygon polygons = 1;

string name = 2;

}

message Timezones {

repeated Timezone timezones = 1;

}

After processing, the file volume has been reduced by about 80MB. It takes about 900MB for this part of the data to be fully loaded into memory. The volume is too large and needs to be reduced. If you look closely at the coordinates in the GeoJSON file, you will find that their point spacing is relatively dense, but there is no need to be so high accuracy in the actual business. Therefore, the first optimization strategy is to reduce the amount of data at the point.

So how to effectively reduce the number of polygon scattering points? The most commonly used algorithm in this field is the Ramer–Douglas–Peucker algorithm:

As shown in the GIF picture display, a complex curve can be simplified to fewer points while maintaining a rough shape. After the filtering of the algorithm, the volume of the file has been reduced to 11MB.

At this point, I wondered whether the 11MB binary file was still a little large in various binary distribution scenarios, so I investigated the coordinate data compression methods and found that Polyline is more suitable. This is Google Maps’ algorithm for compressing continuous coordinates. The principle is that all points except for the first point are stored as offset relative to the previous point, and then the offset is extracted through bit operation to calculate the binary sequence and processed into ASCII. After a single data processing, the time zone polygon data file is compressed to 4.6MB, which is very friendly for binary distribution.

In fact, a usable time zone library has been born here, and the query performance is slightly faster than that of timezonefinder. However, as mentioned in the previous section, business demand scenarios have to face high concurrency traffic pressure. The execution frequency of this part is very high, and the faster the better. Due to the Ray casting algorithm, the time complexity is slower in $O(n2)$, so it is expected that the frequency of this part of execution should be as low as possible, so the index mechanism of the time zone was designed.

According to the experience of administrative divisions, RTree should be enabled here to avoid traversing all polygons. But there is not much better return in the benchmark of global urban data. There are two reasons:

- The total number of time zones is not large, only a few hundred, and there is a 10-fold difference between thousands of administrative divisions of China. In static language, this magnitude traversal does not have an absolute impact on performance.

- The area difference between polygons in administrative divisions is not very large, but there is a big gap between polygons in the time zone. If the search scope is set small, you will not find much time zone information, and if it is adjusted, it will not significantly reduce the number of searches.

So RTree is not suitable.

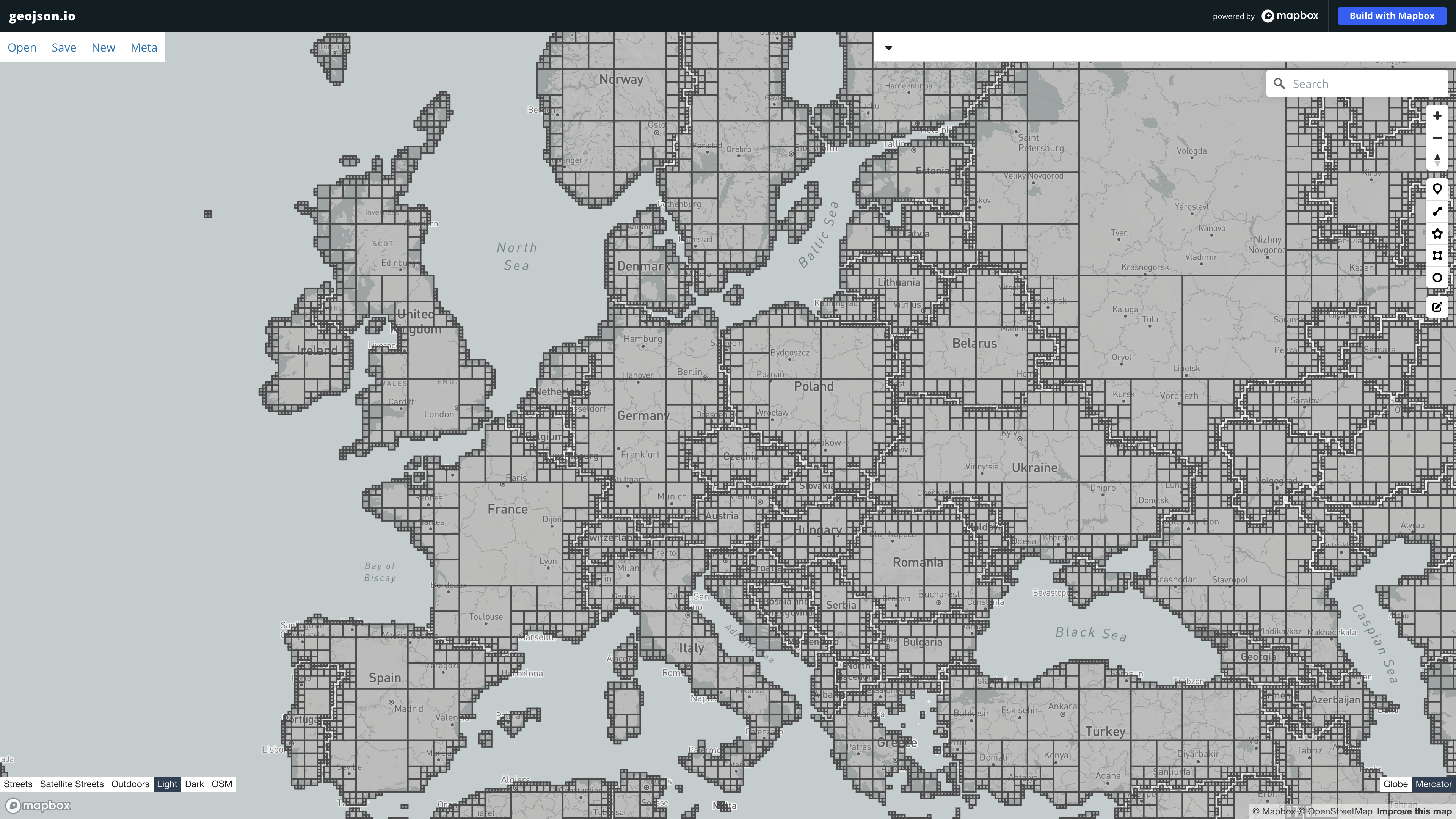

So how to construct index data in the time zone? At the end of October, I was thinking that since polygons can be blurred with embedded quadrilaterals, can they be used to represent approximate shapes with inset polygons? Previously, similar things have been done with Uber H3 on administrative divisions before, but because the parent node of H3 cannot fully contain child nodes, it will leave too much vacuum space, and the effect is not good. Therefore, I turned to the map tile format used for weather station data query(a Chinese introduction here).

┌───────────┬───────────┬───────────┐

│ │ │ │

│ │ │ │

│ x-1,y-1,z │ x+0,y-1,z │ x+1,y-1,z │

│ │ │ │

│ │ │ │

├───────────┼───────────┼───────────┤

│ │ │ │

│ │ │ │

│ x-1,y+0,z │ x+0,y+0,z │ x+1,y+0,z │

│ │ │ │

│ │ │ │

├───────────┼───────────┼───────────┤

│ │ │ │

│ │ │ │

│ x-1,y+1,z │ x+0,y+1,z │ x+1,y+1,z │

│ │ │ │

│ │ │ │

└───────────┴───────────┴───────────┘

It’s amazing and really good. It can represent certain shape information. Moreover, because the tile is designed to use QuadTree, the parent node happens to contain 4 child nodes, which can be aggregated with small tiles without worrying about leaving areas:

At the beginning, this project was attempted in Go, and the project was open sourced as tzf under the MIT License. The functions of data time zone data conversion, data reduction, compression and indexing mentioned above are all command-line tools, in the tzf/cmd directory. The constructed binary data file is published in the tzf-rel repository, using Go’s embed feature.

After Go is ready, I tried to package into a .so file via CGO for Python to

call. Use cibuildwheel to build the

wheel of each platform to avoid compiling during installation. There is no

problem with the basic test, but it is found that the returned object needs to

be recycled manually, otherwise there will be a memory leak

tzf#63. However, calling the CGO do

GC in the Python side will cause the program to execute about twice as slow in

some cases. I asked if there is a more elegant way?

I turned to Rust, good tools such as PyO3 and Maturin, which can be packaged directly into a Python package library without manually recycling objects, and I find in some benchmarks of CPU-intensive scenarios Rust is faster than Go.

So I began to use Rust to load data files, construct map indexes, polygon search and other things in tzf. It is basically smooth. For example, the open source georust/geo has very rich geo computing functions.

As a result, it takes 1,700,000 ns in time zone data processing, compared with 12,000 ns in Go, which is more than 100 times slower. This problem is likely to be the efficiency problem of algorithm implementation, so after an afternoon alarm with the compiler, the geo computing function used in Go was ported to Rust. The project is geometry-rs. Rerun the benchmark.

The result took 3,300,000 ns, which was even slower.

What’s the reason? First of all, I tried not to iterate the object when

cyclicing, but to use index values to extract it. At least there is some

optimization space in Go. I want to try it, but there is no fluctuation in the

result. Then I accidentally noticed that when there were various errors in the

war with the Rust compiler, the point sequence was passed directly to the

function with to_owned, and this object was very large, with millions of

points. Replace this step

with a pointer,

and the performance will come up immediately, about 30000 ns, because the

original Go implementation also constructs an additional layer of pre-indexes

within the polygon data, and Rust does not implement this part of the function,

so it is acceptable to be slower.

After Rust achieved stable performance, it began to encapsulate the Python library tzfpy with PyO3. The whole process was quite smooth. The lazy init was used to initialize the global Finder implementation, so the first call would be slow, and then it would be very fast. That’s it.

Installation and use:

pip install tzfpy

>>> from tzfpy import get_tz

>>> print(get_tz(116.3883, 39.9289))

At present, tzf-rs&tzfpy still uses data that is not compressed by Polyline. Later, it will be switched to further compress the binary volume.

- Translations:

中文